How does a language model understand individual words?#

Thanks to the tokenizer, a text that was originally completely incomprehensible to the computer can be converted into a list of token IDs – in other words, into numbers that the language model can digitally process internally.

Language models (LLMs) process texts internally exclusively on the basis of such tokens.

Note:

For better readability, I will mostly use the term “word” in the following, although technically it always refers to tokens.

But how does a language model (LLM) manage to recognize the meaning of individual words from these bare numbers – and ultimately grasp the sense of entire texts?

How Do We Humans Do It?#

Let’s take the word “cat” as an example.

For us, it is far more than just a sequence of letters: we immediately associate it with ideas like soft fur, fluffy ears, big eyes, and purring sounds. In addition, from our own experience or from stories, we know that cats like to hunt mice, sleep a lot – and don’t always get along well with dogs.

An LLM like ChatGPT tries to capture exactly these connections as well – but in a statistical way.

Learning from Texts: Features Without Labels#

Language models cannot yet observe the world themselves. They have no senses and therefore cannot gather their own experiences. Instead, they learn exclusively from texts – from tens of billions of words, collected from Wikipedia articles, books, forums, websites, and many other sources.

We have already seen that neural networks are true masters at recognizing complex patterns.

During training, the model detects typical patterns and relationships: that “cat” often appears together with terms like “purrs”, “fluffy”, “mouse”, or “animal”.

From this statistical frequency, it derives typical characteristics – for example, that a cat is often described as soft, small, a pet, or playful.

These characteristics are called latent features – because they are not explicitly named or labeled.

The model does not assign fixed tags like “has fur” or “hunts mice”, but instead discovers such patterns on its own based on frequency and context in the text.

Similar to neural networks for image recognition, where one cannot say exactly which edge or which curve makes it recognize a “6”, these features in a language model also cannot be directly read out.

We do not know which internally recognized properties specifically represent a “cat” – but the model learns them from the statistical context of language.

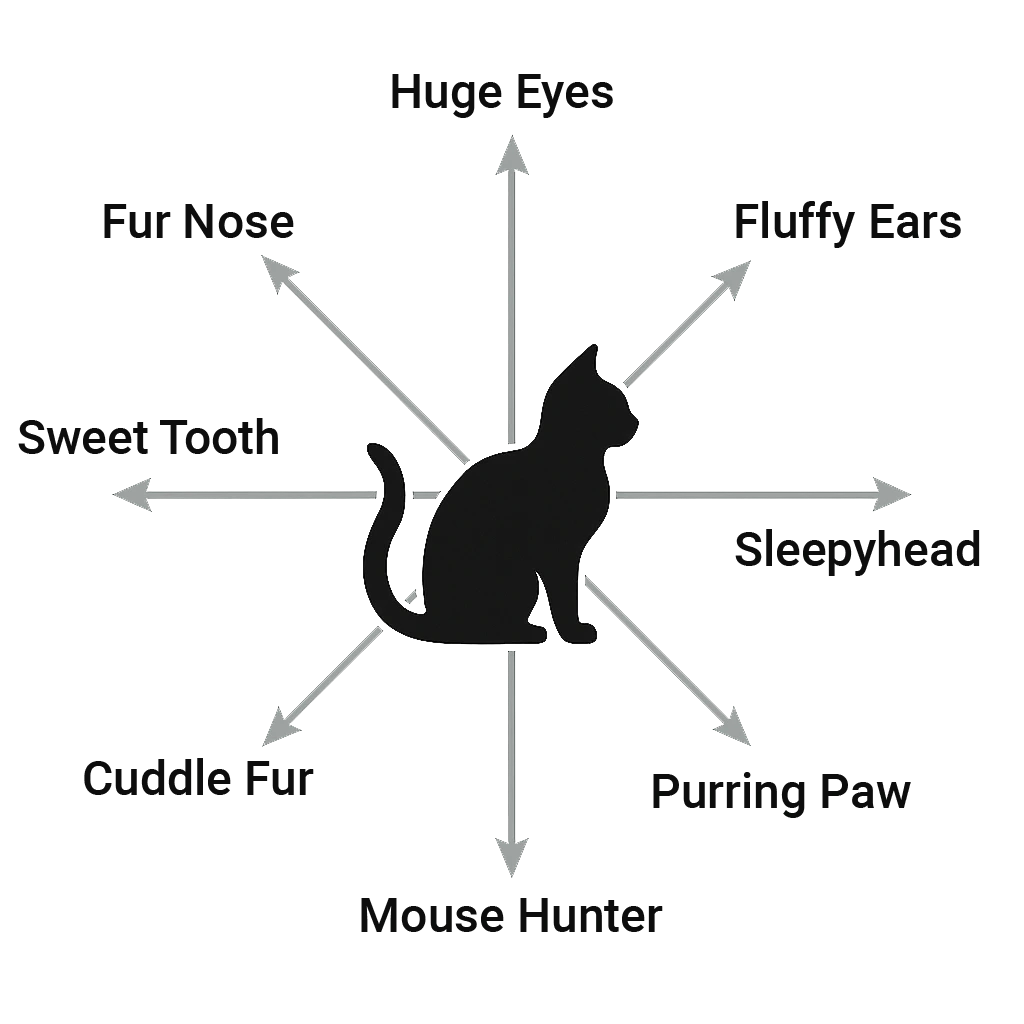

LLMs recognize a multitude of features – in GPT-3.5 there are 12,288 latent features, also called dimensions.

Each word is described by these 12,288 features – this forms the basis for its semantic meaning in the model.

Just to recap: The features (dimensions) are abstract and not directly interpretable for us.

Perhaps one of them represents something like “fluffy” – but these meanings are not labeled, they arise automatically during training of the model.

We humans can only speculate, using certain analysis methods, which properties they represent.

Illustrative – real features are abstract and unlabeled

Dimension Feature Description 1 fluffy / soft Typical feel of the fur 2 pet Often kept in households … … … 12,287 purrs Vocalization when comfortable 12,288 conflict with dogs Typical antagonist in stories

Each individual word is represented as a list of numbers, for example:[0.12, -0.98, 1.57, 0.03, ..., -0.44]

Each of these numbers represents the value of a feature (a dimension).

This list of numbers is called a vector in mathematics – in AI, it is usually called an embedding, i.e., a vector that describes the meaning of a word.

The Embedding Space – Meaning in Numbers#

Each individual word in the text is placed geometrically into a embedding space (also called the feature space), which represents its semantic meaning.

This vector, which defines the position in the feature space and thus describes the meaning of the word, is called an embedding.

Words with similar meanings are closer to each other in this space.

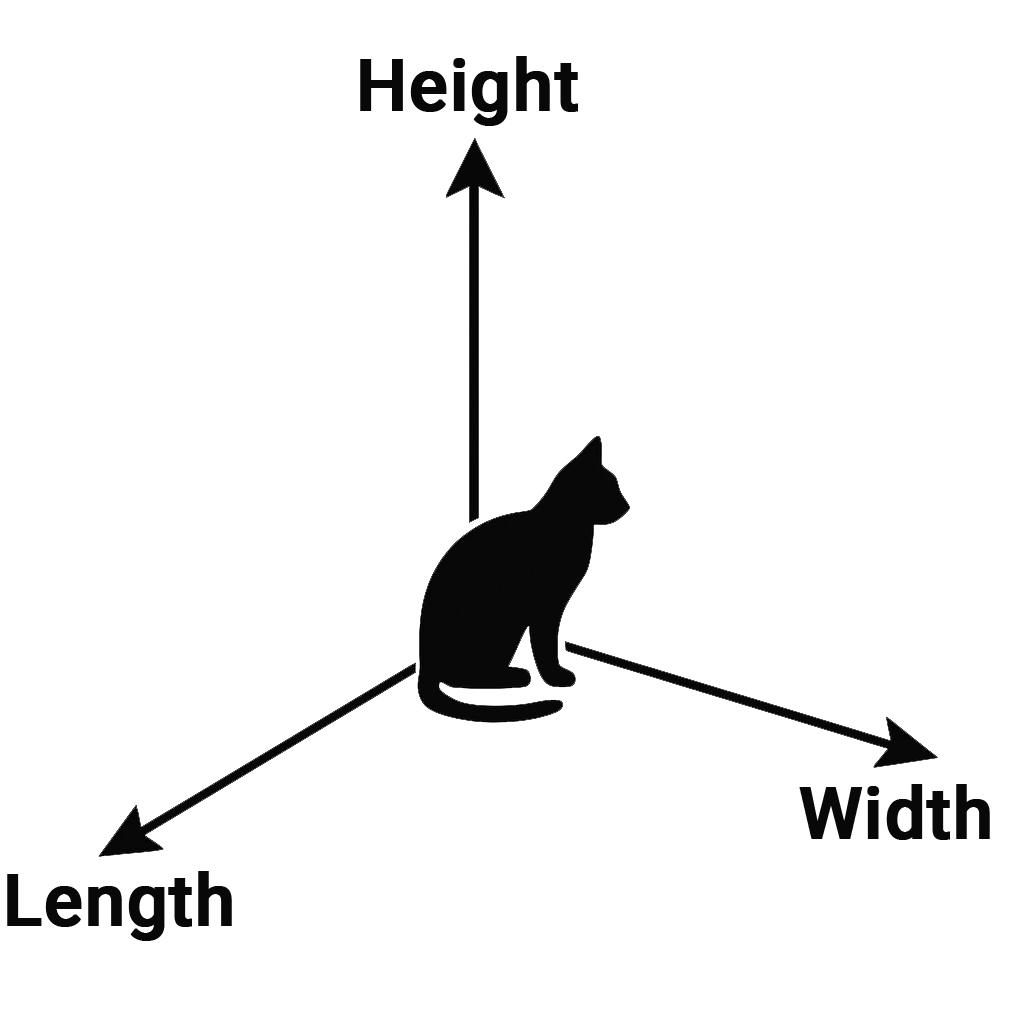

We humans typically know spaces in three dimensions – with the axes width, length, and height.

The feature space in a language model like GPT-3.5, however, has 12,288 dimensions.

Each of these axes represents a latent feature that helps define the meaning of the word.

The illustration shows a simplified representation of eight dimensions of an embedding.

This is not just a metaphor for better visual imagination – the feature space is in fact mathematically represented as a geometric space.

Words with similar features – such as cat, dog, or pet – cluster in one region of the feature space, while terms like car, bicycle, or truck concentrate in another region.

In the geometric vector space, such semantically related terms typically form clusters (groups).

The closer two words are to each other in the space, the more similar they are in content or semantics.

The illustration shows a three-dimensional representation of semantic word relationships.

Similar terms group into recognizable clusters:

On the left, typical pets like dog, rabbit, and guinea pig cluster closely together.

A bit apart, the cat occupies its own place: independent, yet thematically related.

In the center is the carrier box – a neutral link between the animal and vehicle worlds.

On the right, two more clusters form:

Light vehicles such as bicycle and motorcycle – and further out heavy vehicles such as car and truck.

The spatial arrangement – as we already know – is no coincidence:

It results from the statistical patterns that language models detect from billions of words.

The closer terms are in the space, the more similar they are in meaning and usage.

A well-known example illustrates this: the vector difference between “woman” and “man” is similar to that between “queen” and “king”, which points to the feature gender. Likewise, the difference between “car” and “cars” is comparable to that between “dog” and “dogs” – showing that the distinction between singular and plural is also represented in the vector space.

This creates an intuitive, visually tangible landscape from language – with clusters and subgroups.

How similar are two words?#

Classical embedding models like Word2Vec, GloVe, or FastText, as well as modern transformer models, measure semantic similarity based on the spatial proximity of word vectors in the embedding space.

Words with similar context are closer together – independent of grammar or sentence structure.

Basically, there are three ways to measure spatial proximity:

- Euclidean Distance

Here, the geometric distance between two embeddings is calculated across all dimensions.

Intuitively, this corresponds to the “straight line” between two points in the vector space.

For those who like it mathematical:

The Euclidean distance is simply the length of the straight line between two points, calculated using the Pythagorean theorem.

As an example, in 3 dimensions:

$$ d(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y}) = \sqrt{(x_1 - y_1)^2 + (x_2 - y_2)^2 + (x_3 - y_3)^2} $$In the general form for (n) dimensions, it is written more compactly:

$$ d(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y}) = \sqrt{\sum_{i=1}^{n} (x_i - y_i)^2} $$

- Scalar Product (Dot Product)

The similarity of words can also be understood through the angle and the length of the vectors of their embeddings.

You can think of it this way: the smaller the angle between the vectors of two words, the more similar their meanings are.

For those who like it mathematical again:

You multiply the individual components (Hadamard product) and then sum the results.

This produces a single value that expresses the semantic similarity.

- close to 0 → hardly any similarity

- positive → semantically similar

- negative → rather opposite

$$ \mathbf{x} \cdot \mathbf{y} = \sum_{i=1}^{n} x_i , y_i $$

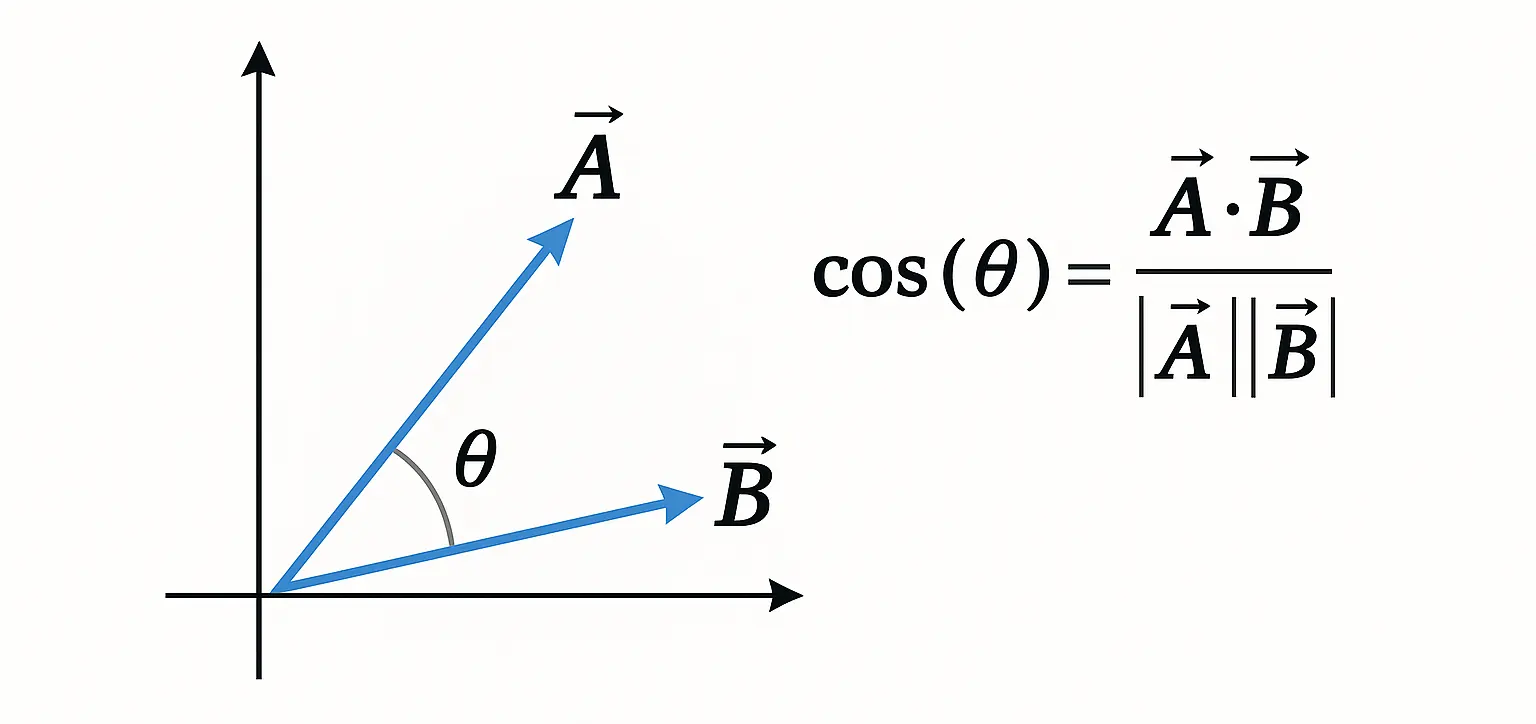

- Cosine Similarity

Cosine similarity goes one step further and is a normalized dot product.

This means: only the angle between the vectors is considered, regardless of their length.

The result always lies between –1 and 1.

As with the other methods, all dimensions of the embeddings are included in the calculation.

For all math enthusiasts:

$$ \cos(\theta) = \frac{ \vec{A} \cdot \vec{B} }{ | \vec{A} | \cdot | \vec{B} | } $$

The formula measures how similarly two word embeddings are oriented in semantic space.

- In the numerator is their dot product – i.e., how strongly they point in the same direction.

- In the denominator is the product of their lengths – which normalizes the values.

The result lies between –1 and 1:

The closer to 1, the more similar the meanings of the words.

Summary#

| Method | Idea | Value Range | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Euclidean Distance | Geometric distance in space | 0 → ∞ | Clustering, distance metrics |

| Dot Product | Considers angle and vector lengths | –∞ → +∞ | Attention, ranking, scores |

| Cosine Similarity | Angle between vectors (normalized) | –1 → +1 | Semantic search, retrieval |

The principle of vector similarity is also used in modern AI applications – for example in semantic search, where terms are compared not only literally but also by their meaning.

Language models also use it to find and process relevant content from large amounts of text.

Modern LLMs like ChatGPT, however, go much further:

They not only compare the semantic closeness of words, but also take into account grammar, sentence structure, and context.

We will take a closer look at how this works in the next sections.

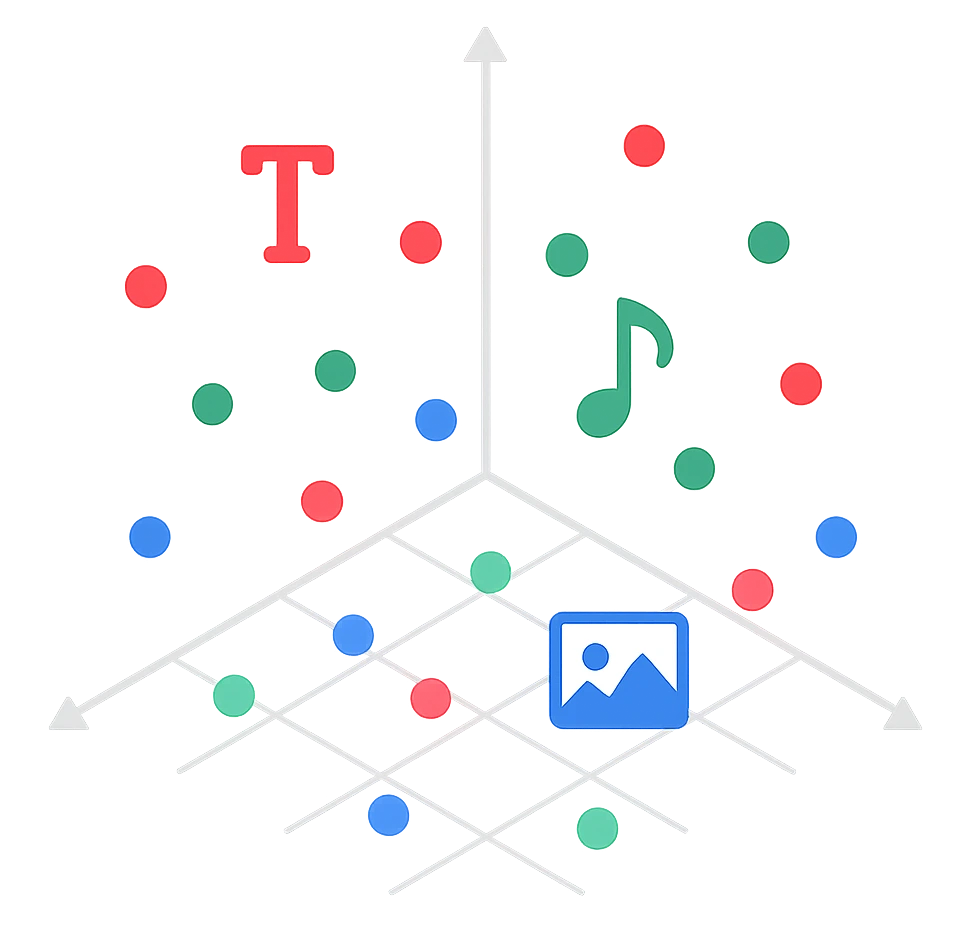

More Than Language: Multimodal Embeddings#

Embeddings are no longer limited to “just” language.

In addition to text and tokens, other media types can also be translated into vectors – such as images, audio, or even video.

This allows AI models to capture meaning not only linguistically, but also visually and acoustically.

The embeddings discussed so far refer to word embeddings (more precisely token embeddings).

But the new models from OpenAI, Anthropic, IBM, Meta, and others are multimodal foundation models:

They understand not only text but also images and audio.

The basic principle remains the same:

- Text is broken down into tokens,

- Images into small patches,

- Audio into short time windows (samples).

From these fragments, the models generate vectors (embeddings) and anchor them in semantic spaces.

There are two approaches:

- a shared embedding space for all modalities,

- or separate spaces, which are aligned during training so that they are compatible and can be directly compared.

This enables the models to work cross-modally – matching an image with a text description or linking a sound with a written term.

In this way, a multimedia understanding of content emerges.

A simple example makes this tangible:

- Text → Image: The input “a cat in a carrier box” retrieves exactly the matching images from an image database.

- Image → Text: A photo of the same scene leads to an automatically generated description of the image in words.

This way, multimodal foundation models link content in both directions and create connections between text, image, and audio.

© 2025 Oskar Kohler. All rights reserved.Note: The text was written manually by the author. Stylistic improvements, translations as well as selected tables, diagrams, and illustrations were created or improved with the help of AI tools.