Python is a programming language designed for fast and readable software development. Beyond general-purpose programming, Python plays a central role in modern artificial intelligence and data science. Most leading AI frameworks and libraries—used for machine learning, deep learning, and data analysis—are built around Python, making it the dominant language in today’s AI ecosystem. Its simple syntax, large ecosystem, and strong community support allow researchers and engineers to prototype, train, and deploy intelligent systems efficiently.

- A Python overview

- Python installation and development tools

- Variables

- Built-in Data Types

- Basic maths

- Strings

- Regular Expressions (Regex)

- Conditional statements

- While and for loops

- Introduction to Python Functions

- Variable Scope in Python

- Lists, Tuples, and Dictionaries

- Numerical Computing with NumPy

- Introduction to Object Oriented Programming

A Python overview#

Easy to set up and multi-OS support#

- The PSF (Python Software Foundation ) has streamlined the Python installation process. Just download the correct interpreter for your environment, install it and start programming.

- Python can run on multiple OS, write your code once and share it among platforms, Mac OS X, Windows, Linux, and others.

Python an interpreted language#

- Interpreted languages are easier for developing and testing. Although a bit slower than compiled languages, they are faster in getting projects to deployment.

Python does not require manual compilation. Source code is automatically compiled into bytecode and executed by the Python Virtual Machine.

| Compiled language: like C | vs. | Interpreted language: like Python |

|---|---|---|

| <=> |  |

Python is dynamic typed#

Python is a Dynamic Typed programming language. Variable types do not have to be declared prior to assignment, such as an int integer, str string or float float. Dynamic type has the advantage to assign any type value to a variable automatically.

Static type#

int my_variable = 3int my_variable = 'car'ERROR!

Dynamic type (Python)#

my_variable = 3my_variable = 'car'OK!

Python a laconic language#

This means Python does not have excessive syntax elements.

Below is an example that outputs the phrase "Hello World!" to the screen, one written in Java and the other in Python.

Code in Java#

public class HelloWorld

{

public static void main (String[] args)

{

System.out.println("Hello, world!");

}

}

Code in Python#

print('Hello, world!')

Python’s multipurpose standard library#

Python is a general-purpose programming language, ranging from system administration, database integration, web apps to Data Science. Python can be flexible due to its large standard and 3rd party libraries.

- Python’s standard library https://docs.python.org/3/library/ contains built-in modules (written in C) providing access to system functionality, such as file I/O, otherwise inaccessible to Python programmers.

- In addition to the standard library, there is a growing collection of several thousand components (from individual programs and modules to packages and entire application development frameworks), available from the Python Package Index https://pypi.org/ .

Python installation and development tools#

Interacting with Python is easy. Nowadays, there are many tools available to help developers write in Python.

We can download Python and install it in our system. The Python interpreter comes with a development environment.

- There are several Python editors available, as well as IDEs (Interactive Development Environments).

- We can also use one of several online Python development tools.

Short list of available development tools for Python

| Development tool | Description | Type |

|---|---|---|

| text editor: | a basic system text editor, such as Notepad, can be used for Python development. Limited features | local |

| Interactive Python Interpreter: | is accessed through the command line or IDLE’s interactive shell | local |

| IDLE’s script editor: | it can create, save, edit and run python scripts. The most basic Python editor, easy to use | local |

| Visual Studio Code: | Open source 3rd party development tool, by Microsoft. It offers many features and extensive support | local |

| Python.org shell: | online interactive shell provided by https://www.python.org/shell/ , very basic | online |

| Repl.it: | https://repl.it/ this is a web-based interpreter design for education | online |

| Trinkets: | https://trinket.io/python3 Trinket lets us run and write code in any browser, on any device | online |

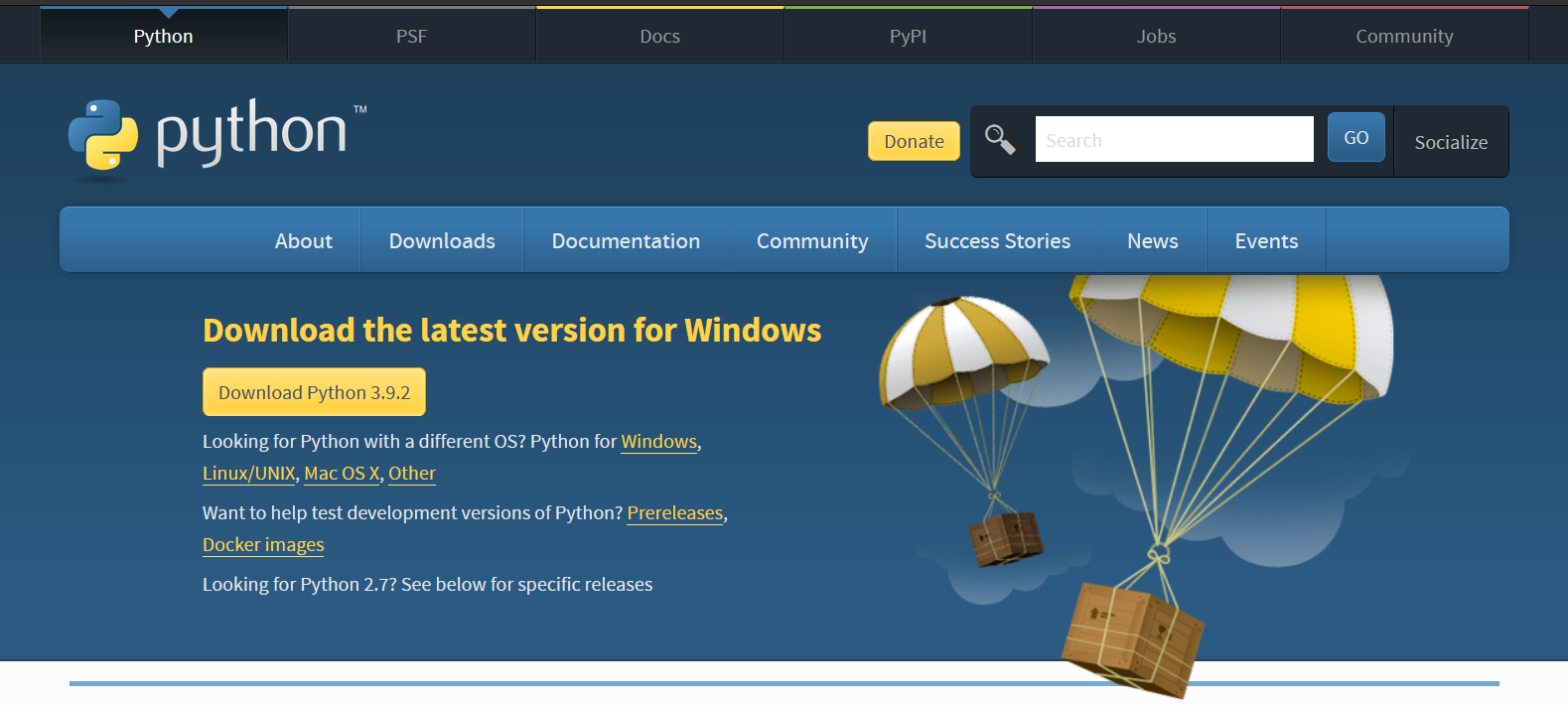

Python installation#

There are pre-compiled packages available for easy installation on different operating systems such as Windows, Linux, UNIX, and macOS.

If we head over to https://www.python.org/downloads/ we can select the correct installation method for any operating system. Most Linux systems come with Python pre-installed.

Using Python version 3.x#

On Windows, once we have installed Python we will be able to write, edit, save and run our scripts in two ways, one, with the interactive prompt, or two, a “text” editor.

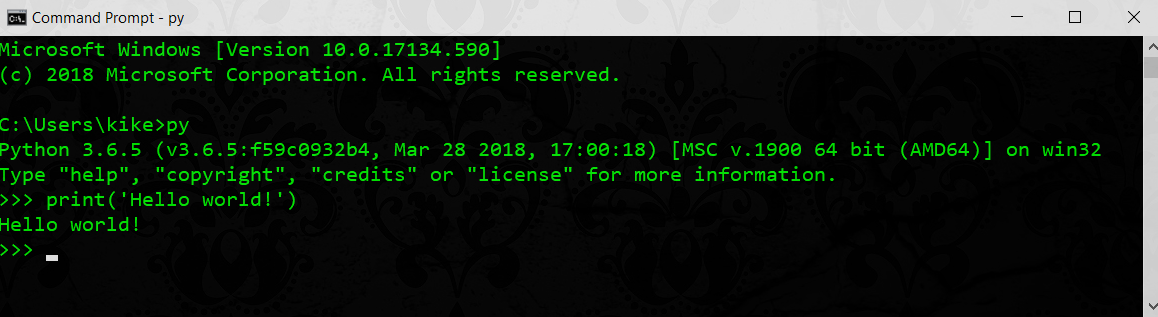

- Command prompt: Interactive Python Interpreter Session

- Python’s IDLE

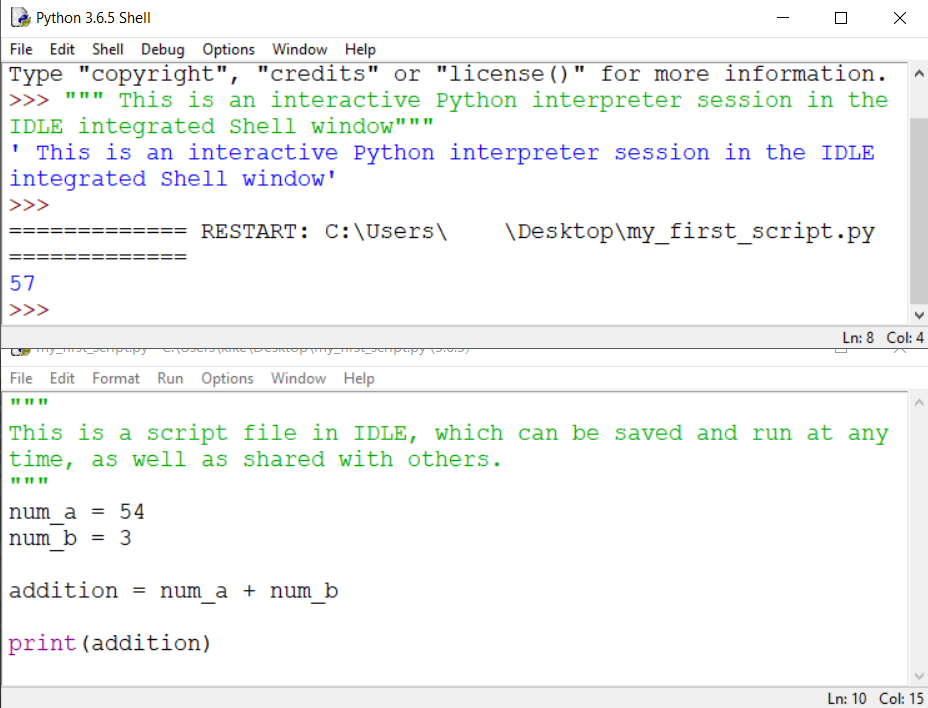

The difference between the IDLE and the console is that IDLE has a graphical interface and looks similar to a text editor.

We can launch Python interactive prompt from the command line by typing “python”, to choose a specific version of Python type “python X” where “X” is the version number (e.g. “python3” for version 3).

Interactive Python Interpreter Session#

It can be started by calling the command prompt, console, or online (the name and launching method will depends on the Operating System).

It is possible to write a program using just a Python interactive session, but not recommended. Consider the interpreter as an “on the fly” testing tool for coding ideas.

Python IDLE#

IDLE is Python’s editing software, a basic easy to use development tool. IDLE comes installed with the Python interpreter.

Online development tools#

There are many solutions available on the Internet for fast development and testing.

Online editors, commonly used for teaching and sharing code. Online editors offer different features. We can choose one that best fits our needs.

“Hello World!” our first program#

We can use a Python interpreter session to write code interactively.

Let’s write our first program by printing "Hello World!" string on the computer screen.

Launch the command prompt in our system, with Python already installed.

Start a Python interactive session by typing the following in the command prompt, > python.

C:\\Users\\you>python

Python 3.9.1 (tags/v3.9.1:1e5d33e, Dec 7 2020, 17:08:21) [MSC v.1927 64 bit (AMD64)] on win32

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>>

We have an interactive session going, now type the following (and hit Enter):

>>> print("Hello World!")

Hello World!

>>>

There, we wrote our first program!!!

Using IDLE, the Python editor#

IDLE comes installed with the Python interpreter. IDLE written in Python, come with an interactive shell and a script editor.

We are going to create and save a script file.

- Open IDLE

- Create a new script file

- Write a script

- Save the file

- Run the script

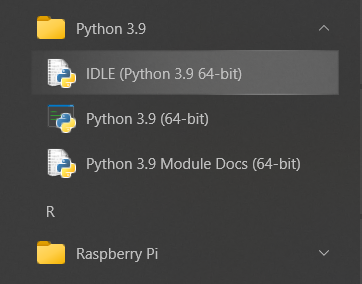

To open IDLE, navigate to our application launcher. Listed should be a new Python folder, with IDLE listed as well.

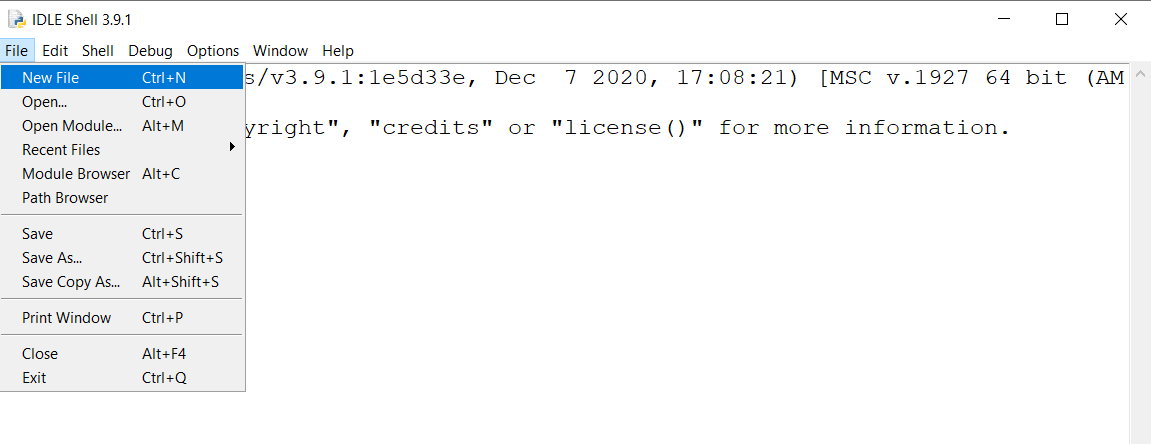

IDLE opens with an interactive session ready to use

Create a new script file by going under the “File menu” and choosing “New File”.

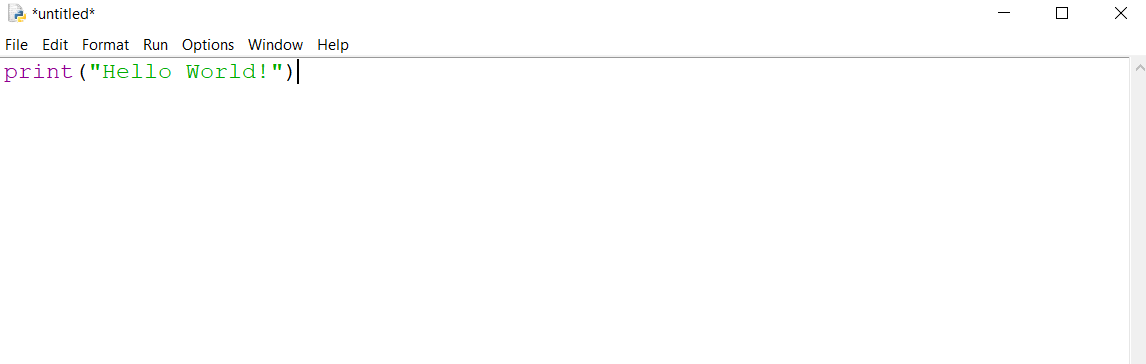

A new “untitled” window will pop up. We will write our “hello world” script.

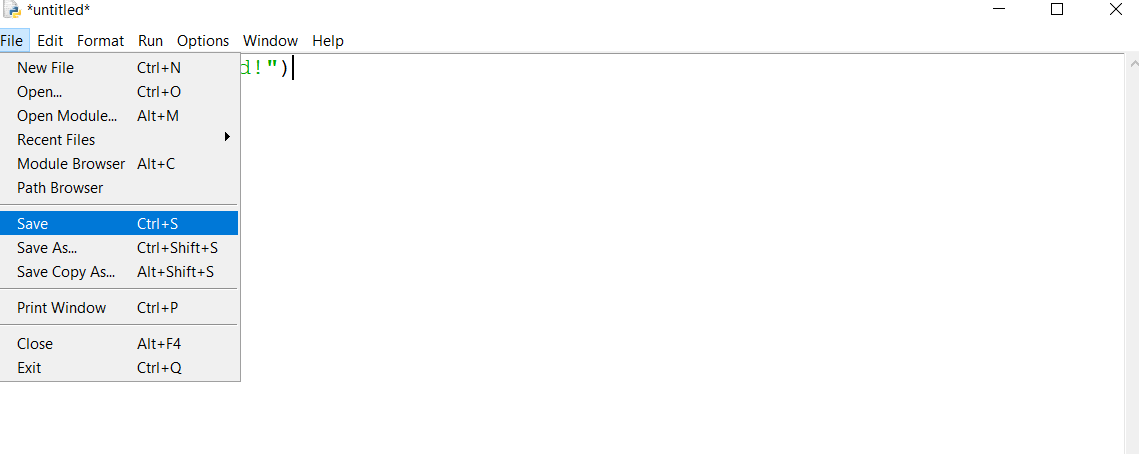

Save the script file. Name the file hello_world.py, notice the file extensions. All python scripts have the same file extension, .py.

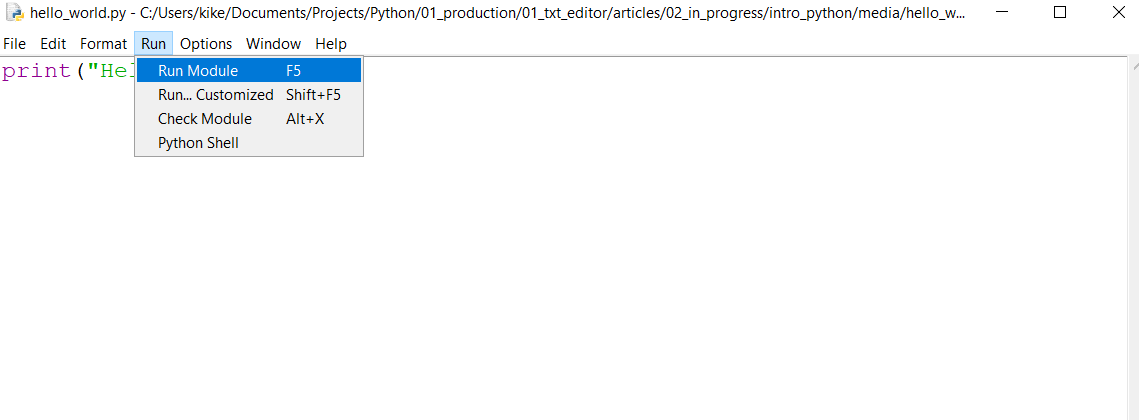

To run the program, go under the “Run” menu select “Run Module”.

IDLE will launch an interactive session and run our script!

Whatever editor we choose to use, is based on the same idea.

Variables#

Variables are temporary “containers” holding data. Variables allow us to change assigned values as our application executes.

>>> my_var = 230

>>> my_var

230

variable assignment#

We may assign the same value to multiple variables using the following syntax:

>>> a = b = c = d = f = "Hello World!"

when we request the variables, the Python interpreter will return the following:

>>> a

'Hello World!'

>>> c

'Hello World!'

>>> f

'Hello World!'

variable types#

Python is a dynamically typed programming language, meaning we don’t have to declare what type each variable is.

any_var_type = 'this is a string'

We assign the value to the variable, and Python can figure out the variable type.

We can always ask Python to return the variable type by using the type() function:

>>> type(any_var_type)

<class 'str'>

Python supports optional type hints for better readability and tooling.

age: int = 30

name: str = "Michael"

Type hints do not enforce types at runtime. They are mainly used by editors and static analysis tools.

variable naming convention#

A variable can have a short name, such as x and y or a more descriptive name such as age, name, product_id.

Variables must start with a letter or an underscore.

x = 45_y = 24

Variables must contain only letters, digits, or underscores.

- (A-z, 0-9 y _)

my_variable_A = 3456- A variable name can not start with a number

9true_var = 45 # invalid

true9_var = 45 # valid

- Variable names are case sensitive

size,SizeandSIZEare three different variables

size = 34

Size = 40

SIZE = 56

- Here are a few examples of illegal variable names

2var

var-bar

foo.loo

@var

$var

Reserved Python 3 Keywords#

Apart from the rules mentioned earlier, it is critical to note, Python has a variety of reserved “keywords” which cannot be used as variable names:

and assert break class continue def del elif

else except finally for from global if import

in is lambda not or pass raise return

try while yield

This list reflects Python 3 keywords. Built-in functions such as print or exec are not keywords.

We will learn the use of keywords as we cover other topics.

Built-in Data Types#

Every value in Python has a datatype and is considered an Object

- Data Types are Classes and

Variables are instances (objects) of these Classes - There are two classes of Data Types, Primitive and Non-primitive. We will cover non-primitives at a later point.

Primitive data types#

Primitive assignment#

- We can assign any primitives to a variable by using the equal sign

=

We can verify data type on any object by using the type() function, type(‘What type am I?’)

>>> foo = True

>>> foo

True

>>> type(foo)

<class 'bool'>

Type() swap#

Python is flexible allowing us to convert strings to integers and integers to strings:

>>> to_string = str(100)

>>> print(to_string, type(to_string))

100 <class 'str'>

>>>

>>> to_interger = int("234")

>>> print(to_interger, type(to_interger))

234 <class 'int'>

>>>

⚠️ Avoid overwriting Python built-in names.

# BAD: overwrites a built-in function

int = 10

# GOOD

i = 10

Overwriting built-in names like int, list or str can break your code and should always be avoided.

Strings and quotes#

- We may use double " or singular ’ quotes to denote string values.

- They are interchangeable.

- The quotes must match.

one = "Spam"

two = 'Single Spam'

three = """Multi-line Spam"""

four = '''Individual Spam'''

The following strings are not allowed because the opening quotes do not match the closing ones. The Python interpreter will return an error in this case.

"foobar''''zooloo"""

>>> "foobar'

File "<stdin>", line 1

"foobar'

^

SyntaxError: EOL while scanning string literal

We may have embedded quotes within a set of encapsulating quotes.

one = "'foobar'"

two = '... and she screamed "zooloo" as loud as she could'

print(two)

multi-line strings#

We may use multi-line strings to store large blocks of text in Python.

Multi-line string is a string enclosed by triple quotes instead of single ones.

multi_line_string = """1. First line

1. Second line

2. Third line

3. Fourth line

"""

We will cover strings and built-in functions in more detail later on.

Quiz#

- What is the name of this

=operator? - How to convert a digit

3.14into a string'3.14'? - What’s wrong with the following piece of code:

variable = "john smith'? - What about this one:

variable = "foobar"""

Quiz answers#

- assignment operator

str(3.14)- singular and double quotes do not match each other

- the number of quotes does not match

Basic maths#

Python has many built-in arithmetic operators. It supports all of the math operations we would expect. The basic ones are:

- Addition

- Subtraction

- Multiplication

- Division

Other ones include the exponentiation and modulo operators, which we will see in a moment.

Numbers#

Numbers in Python can be an integer, floats boolean and complex numbers. We will explore complex numbers at a later point.

Integers: positive or negative whole numbers with no decimal point

- 1, 4, 25, 456, -777777

Floats: represent real numbers and are written with a decimal points.

- 1.0, 4.22, 25.098, 456.1, -777777.7

Booleans: are True or False (1 or 0).

- a binary choice,

True == 1

- a binary choice,

Assume the following is true:

a = 3

| Operation name | Short notation | Long notation | Value of a | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Addition | a += 1 | a = a + 1 | 4 | |

| Subtraction | a -= 1 | a = a - 1 | 2 | |

| Multiplication | a *= 2 | a = a * 2 | 6 | |

| Division | a /= 2 | a = a / 2 | 1.5 | Returns decimal values or float numbers |

| Modulo | a %= 2 | a = a % 2 | 1 | Returns an integer remainder of a division |

| Exponent | a **= 2 | a = a ** 2 | 9 | Similar to a^2 in regular maths |

| Floor division | a //= 2 | a = a // 2 | 1 | returns floor-divided value |

| Negation | a = -a | a = 0 -a | -3 | Returns the same value with an opposite sign |

Each operation has a short and long notation. Conventionally we can use the short form as it is faster to write.

a += 1is the same asa = a + 1whereais3then the result would be4

Addition#

Any arithmetic operators execute the same as they would on paper. Just much faster reading, calculating, and writing.

- Addition: adds values on either side of the operator.

>>> a = 4

>>> b = 2

>>> a + b

6

>>>

Subtraction -#

Subtracts right hand operand from left hand operand.

From the previous slide we know that

a = 4b = 2

Subtracting b - a, we get

>>> a - b

2

>>>

Multiplication *#

Multiplies values on either side of the operator

If we multiply two integers, the result is of the data type

int. If one of the numbers is a decimal, Python will return afloatvalue.

>>> a * b

8

>>>

Division /#

Divides the left-hand operand 4 by the right-hand operand 2.

>>> a / b

2.0

>>>

Modulus %#

Divides the left-hand operand 4 by the right-hand operand 2 and returns the remainder

>>> a % b

0

>>>

Exponent **#

Performs an exponential (power) calculation on operators.

a**bor 4 to the power 2

>>> a ** b

16

>>>

Floor Division //#

The floor division operator // rounds the result down toward negative infinity, not simply truncating the decimal part.

>>> a // b

2

>>>

Operator precedence#

The order of execution of mathematical operations in Python is similar to the one in conventional maths.

In arithmetic there are three general operator priority levels:

- Exponents and roots

- Multiplication, division, and modulus

- Addition and subtraction

Let’s look at a math operation and the order of execution.

d + e * f + g

>>> d = 2

>>> e = 3

>>> f = 4

>>> g = -1

>>> h = d + e * f + g

>>> h

13

>>>

Higher-order operations are performed before the lower ones.

All the operations of the same order are executed one by one left to right.

2 + 3 * 4 -1 equals 13.

First,

3is multiplied by4(which is12)- Then

2 + 12 + - 1is performed.

- Then

Strings#

Strings are among the most popular types in Python. We have used strings extensively in our course.

We are going a bit more in-depth to describe and show many things that strings can do.

As mentioned before, strings are immutable primitive types.

Strings are a sequence of characters.

We will cover the following topics in this lesson.

- String characters in Python

- Creating a string

- Removing and “editing” strings

- Strings indexing and slicing

- String iteration

- String Operators

- String Methods

- String formatting

String characters in Python#

In Python, strings are represented as a sequence of immutable Unicode characters. Unicode includes every character in all languages.

string = "Sparse is better than dense."

Each character has a numerical value. We will have to elicit the help of a couple of built-in functions, ord() and chr().

ord(): Converts character to an integer.

>>> ord('n')

110

>>> ord('N')

78

chr(): Converts an integer (Unicode code point) to its corresponding character.

>>> chr(56)

'8'

>>> chr(123)

'{'

The string object#

We can turn a number into a string by using the built-in function str().

>>> type(45)

<class 'int'>

>>> type(str(45))

<class 'str'>

>>> '4' in str(45)

True

Creating a string#

Strings are created by wrapping characters in single, double, or triple quotes.

Notice, the quotes must be the same at the start and end of the string.

str_single = 'This is a string'

str_double = "This is a string"

str_triple = """ This is a string """

Removing and “editing” strings#

Strings can not be edited as they are immutable, but we can reassign a new string to the same variable.

>>> string = 'aeio'

>>> string

'aeio'

>>> string = 'aeiou'

>>> string

'aeiou'

We can delete an entire string using the keyword del. We can not remove an individual character from a string.

>>> del string

>>> string # no longer exists

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

NameError: name 'string' is not defined

Strings indexing and slicing#

Strings as a series of positional characters are indexed from left to right, starting with the number 0.

Right to left with negative numbers starting with -1.

| P | Y | T | H | O | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| -6 | -5 | -4 | -3 | -2 | -1 |

We can count the number of characters in a string using the len() function.

>>> len('python')

6

We can access a character by specifying its string index. We write the string followed by square brackets [n] where n is the index number of the character we want to access.

>>> 'python'[2]

't'

Inversely we can access the character from right to left using negative numbers, indexing backward.

>>> 'python'[-4]

't'

String slicing#

Slicing is designed for extracting an entire section in a single action, creating a new object with the result.

>>> 'python'[1:4]

'yth'

In the example above, we sliced from index 1 up to (but not including) index 4. [1:4].

| Y | T | H | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

Let’s assign the string "python" to the variable f to simplify our examples.

f = 'python'

If we omit the first index, Python assumes it starts at 0.

>>> f[:3]

'pyt'

>>> f[0:3]

'pyt'

If we omit the second index [n:], Python will slice from n to the end of the string.

>>> f[2:]

'thon'

>>> f[-4:]

'thon'

>>> f[2:len(f)]

'thon'

To return the complete string, we can write it as follow.

>>> f[:]

'python'

If we pass two indexes of equal value [n:n] or overlapping indexes Python will return an empty object.

>>> f[2:2]

''

>>> f[2:-4]

''

Python slicing has a third index used to indicate stepping or by increments of n.

[x:y:n]

>>> f[::2]

'pto'

We can also give a negative index for stepping [x:y:-n]. Python will step backward through the string.

>>> f[5:0:-2]

'nhy'

Without a first or second index, the string indexes get reversed.

To reverse a string we can use the following format [::-1].

>>> f[::-1]

'nohtyp'

String iteration#

We can iterate through each character of a string by using a for loop.

>>> f = 'python'

>>> for l in f:

... print(l)

...

p

y

t

h

o

n

String Operators#

Several operators can be used with strings adding even more flexibility to strings.

| Operator | Description |

|---|---|

+ | Joins two or more strings together. |

* | Creates multiple copies of string. |

in | Membership of string in another string. |

not in | This is the opposite of the in operator. |

The + operator#

The + can join two or more strings together.

>>> st1 = 'The first string'

>>> st2 = 'The second string'

>>> new_st = st1 + st2

>>> print(new_st)

The first stringThe second string

We can add another string to add space between the st1 and st2

>>> st1 + ' ' + st2

'The first string The second string'

The * Operator#

The * generates multiple copies of a string. It works on any string.

>>> '-' * 8

'--------'

>>> '123' * 4

'123123123123'

The in Operator#

Test membership of s string in another string. It returns a boolean True or False.

>>> master_st = 'Beautiful is better than ugly.'

>>> 'ugly' in master_st

True

The not in Operator#

The not in operator is the opposite of the in operator.

>>> 'ugly' not in master_st

False

>>> 'apple' not in master_st

True

String Methods#

Just as Python has built-in functions, procedures when called, perform specific tasks on an object, ie.

len('hello').

Python also offers built-in methods, much like functions, to perform a procedure on a specific object.

The way to call a string method is to write the object followed by .method_name().

Because strings are immutable when we use a method, it returns a copy of the original string.

There are over 40 built-in string methods available we are just going to cover a few.

For a full list of string methods, please see the Python documentation.

.capitalize()#

This method capitalizes a string.

>>> x = 'hello'

>>> x.capitalize()

'Hello'

.upper()#

Use this method to turn a string to all upper cases.

>>> u = 'hello world'

>>> u.upper()

'HELLO WORLD'

.lower()#

It returns a string with all lower case.

>>> y = 'ReaDAbiLity CouNts.'

>>> y.lower()

'readability counts.'

.title()#

It will turn a string into a title.

>>> t = 'Beautiful is better than ugly.'

>>> t.title()

'Beautiful Is Better Than Ugly.'

Python also offers some Methods specifically for searching for a substring in a string.

.count()#

This method returns the number of occurrences of a substring in a string.

>>> 'Now is better than never'.count('e')

4

>>> 'Now is better than never'.count('tt')

1

We can also limit the count to a specific range by passing a starting and ending index.

>>> x = 'Now is better than never'

>>> x.count('e', 9, 24)

3

.startswith() and .endswith()#

These two methods determine if a target string starts, or ends, with a particular substring. The methods will return True or False.

.startswith()#

>>> x = 'Now is better than never'

>>> x.startswith('Now')

True

>>> x.startswith('is')

False

.endswith()#

>>> x.endswith('ever')

True

Formatting methods allow us to enhance a string.

.center()#

We can center strings on a given field of spaces.

>>> 'Beautiful'.center(15)

' Beautiful '

We can also assign a fill character inserting the character as an argument.

>>> 'Beautiful'.center(15, '~')

'~~~Beautiful~~~'

.ljust() and .rjust()#

Aside from centering a string, we can also justify it left or right justify.

>>> 'Beautiful'.ljust(15)

'Beautiful '

>>> 'Beautiful'.rjust(15)

' Beautiful'

We can also fill the range with a character.

>>> 'Beautiful'.ljust(15, '-')

'Beautiful------'

>>> 'Beautiful'.rjust(15, '-')

'------Beautiful'

.strip(), .lstrip() and .rstrip()#

Another useful string method are the .strip(), .lstrip() and .rstrip()

When we don’t specify an argument, Python will strip all the leading and trailing spaces depending on the type of strip method we use.

>>> n = ' Beautiful '

>>> n.strip()

'Beautiful'

>>> n.lstrip()

'Beautiful '

>>> n.rstrip()

' Beautiful'

We can specify the characters to strip.

>>> 'purity/?'.rstrip('/?')

'purity'

>>> 'Mr. Brown'.lstrip('Mr. ')

'Brown'

⚠️ Warning: lstrip() / rstrip() do NOT remove substrings. They remove all characters found in the given string, from the left/right.

.replace()#

We can use the .replace() method to replace an ‘old’ substring for a ’new’ one. Since strings are immutables, Python creates a copy with the new changes.

>>> 'Mr. Sophie Brown'.replace('Mr.', 'Mrs.')

'Mrs. Sophie Brown'

We can also specify the number of times we can replace a substring, from left to right.

When we don’t specify the count, the method will replace every instance of the ‘old’ word.

>>> 'right.move.right.now'.replace('right','left', 1)

'left.move.right.now'

String formatting#

Python has three types of string formatting, expression, method, and f-string.

Note: variables examples in the table below

var_1 = 'Easy'var_2 = 'Python'

| Syntax | type |

|---|---|

| print(’%s = %s’ % (var_1, var_2)) | Expression |

| print(’{} = {}’.format(var_1, var_2)) | Method |

| print(f’{var_1} = {var_2}’) | fstring |

| Easy = Python | <= prints |

String formatting expression#

Formatting expression is the oldest type of formatting available since the start of the language based on the programming language C.

We will continue to see this type of formatting around.

>>> xx = 'her'

>>> 'I spoke to %s yesterday' % xx

'I spoke to her yesterday'

With the formatting expression, one must specify the type of object to replace.

In the previous case, we used %s where s stands for string. Below is a partial list of types.

| Code | Meaning |

|---|---|

| s | String (or any object’s str(X) string) |

| c | Character (int or str) |

| d | Decimal (base-10 integer) |

| i | Integer |

| f | Floating-point decimal |

We may look at the Python documentation for more information on formatting expressions.

String formatting method#

The formatting method uses a method-call to format a string object.

The string becomes a template, and the format method argument passes values to the template.

The values passed as arguments in the formatting method are positional.

>>> string_template = '{} is {} than {}.'

>>> string_template.format('Beautiful', 'better', 'ugly')

'Beautiful is better than ugly.'

We can assign the order for values in a string by specifying the methods argument index.

>>> string_template = '{1} is {0} than {2}.'

>>> string_template.format('Beautiful', 'better', 'ugly')

'better is Beautiful than ugly.'

With this method, we can also format numbers.

>>> 'pi with three decimals {:.3f}'.format(3.14159265)

'pi with three decimals 3.142'

We can also arrange a string in a given space for better display by using the format method.

"|{:<12}|{:^12}|{:^12}|".format('Name','Date','Price')

'|Name | Date | Price |'

There are many string formatting available to use with the .format() method.

Please see the documentation for more detailed use.

Formatted String Literal (f-string)#

The f-string was introduced in Python 3.6 and is the recommended string formatting method in modern Python.

By simply prefixing the string with the letter f'sample {var}'.

We can add curly brackets {} inside the strings.

Placing a variable inside the curly brackets, the interpreter will put the value inside the curly brackets.

>>> a = 24

>>> b = 45

>>> f'The result for {a} + {b} = {a + b}'

'The result for 24 + 45 = 69'

The f-string format is extensive, but we can see more in the Python documentation.

Python provides an extensive toolbox to handle string from starting at a very granular level.

We covered the most relevant aspect of strings.

Numerical Computing with NumPy#

NumPy is the fundamental library for numerical computing in Python.

It provides fast, efficient array operations and forms the foundation of most AI and machine learning frameworks such as PyTorch and TensorFlow.

Importing NumPy#

import numpy as np

NumPy is commonly imported using the alias np.

NumPy Arrays#

A NumPy array is a collection of elements of the same data type, stored in contiguous memory for efficient computation.

a = np.array([1, 2, 3])

print(a)

Vectorized Operations#

Unlike Python lists, NumPy arrays support vectorized operations. This means operations are applied element-wise without explicit loops.

a = np.array([1, 2, 3])

b = np.array([4, 5, 6])

print(a + b)

print(a * 2)

NumPy arrays behave differently from Python lists when applying operators.

lst = [1, 2, 3]

arr = np.array([1, 2, 3])

print(lst * 2) # list replication

print(arr * 2) # numerical multiplication

Common Array Properties#

a = np.array([[1, 2, 3],

[4, 5, 6]])

print(a.shape)

print(a.ndim)

print(a.size)

- shape: dimensions of the array

- ndim: number of dimensions

- size: total number of elements

Basic Aggregations#

NumPy provides fast aggregation functions commonly used in data analysis.

a = np.array([1, 2, 3, 4])

print(a.sum())

print(a.mean())

print(a.min())

print(a.max())

Indexing and Slicing#

NumPy supports slicing similar to Python lists, but extended to multiple dimensions.

a = np.array([[1, 2, 3],

[4, 5, 6]])

print(a[0, 1]) # element

print(a[:, 1]) # column

Why NumPy is Essential for AI#

NumPy arrays represent vectors, matrices, and tensors.

Most AI frameworks build on NumPy-like abstractions to perform efficient numerical computations on large datasets.

⚠️ NumPy arrays are homogeneous (all elements have the same type). If you need mixed data types, use Python lists instead.

NumPy is optimized for numerical data, not for general-purpose data storage.

Regular Expressions (Regex)#

Regular expressions allow advanced pattern matching and text preprocessing.

They are widely used in data cleaning, log analysis, and natural language processing (NLP), making them an essential tool for AI and machine learning applications.

Python provides regular expression support through the built-in re module.

import re

The search() function scans a string for a pattern and returns the first match.

text = "Machine learning is powerful"

match = re.search("learning", text)

if match:

print("Match found")

If no match is found, search() returns None.

match = re.search("learning", text)

if match:

print(match.start(), match.end())

The start() and end() methods return the position of the match in the string.

findall() returns all non-overlapping matches of a pattern.

text = "Data drives AI and data science"

matches = re.findall("data", text.lower())

print(matches)

findall() returns a list of matched substrings.

sub() replaces parts of a string that match a pattern.

text = "User123 logged in at 10:45"

cleaned = re.sub(r"\d", "", text)

print(cleaned)

Regular expressions often use raw strings to avoid escaping backslashes.

pattern = r"\d+"

Common regex patterns:

| Pattern | Meaning |

|---|---|

. | any character |

\d | digit (0–9) |

\w | word character (letters, digits, underscore) |

\s | whitespace character |

+ | one or more |

* | zero or more |

? | optional (zero or one) |

^ | start of string |

$ | end of string |

⚠️ Regular expressions can quickly become complex. For simple string operations, prefer built-in string methods when possible.

In AI and NLP workflows, regular expressions are commonly used for: • cleaning raw text data • removing unwanted characters • extracting structured information • preprocessing input before tokenization

Conditional statements#

We have seen the sequential execution of statements. A program needs to have logic to be flexible and usable.

We are going to introduce the if conditional statement, allowing our programs to have logic.

For example, we can evaluate an integer to see if it is odd or even, and depending on the result, a program can execute a particular statement.

Boolean expressions#

The simplest way to evaluate conditional statements is by using boolean expressions.

The most common boolean expressions in Python are True and False. Booleans are reserved keywords and can not be variable names.

True and False evaluate numerically to 1 and 0, but their actual type is bool, not int.

>>> int(True)

1

>>> int(False)

0

Although True and False have values of 1 and 0, they are not integers. They belong to their class.

>>> type(True)

<class 'bool'>

>>> type(False)

<class 'bool'>

Yet, we can write the following statement in Python, and it would be valid. This is possible, but not recommended in real-world code.

>>> double = True + True # 1 + 1 = 2

>>> double * 4

8

>>> double * False

0

Boolean Operators#

We can do multiple comparisons by using a boolean operator, let’s use or, boolean because when used, it will return either True or False

Using the boolean operator,

or, we can test if any of the two comparative statements below areTrue.- It returns

Truebecause one condition passed the test,n < 10.

- It returns

>>> n = 5

>>> 5 < n or n < 10

True

When we use

andboth comparative statements tested need to pass for the operation to beTrue.In this case, is

False.Because

5 < 5isFalse- Immediately returning

False.

- Immediately returning

>>> n = 5

>>> 5 < n and n < 10

False

An alternative to using the comparison

andabove, remove theandcomparison and one the variablen.- This

5 < n and n < 10is the same as5 < n < 10

- This

>>> n = 5

>>> 5 < n < 10

False

By combining conditional statements and boolean evaluation, we can write pretty powerful programs.

The if Conditional statement#

Conditional statements, such as if, allow us to make choices based on preconditioned criteria.

We can use other comparison operators to check the validity of these criteria, such as equality ==, allowing us to test for validity.

Python uses the special value None to represent the absence of a value.

line = None

if line is None:

print("No value set")

Always use “is” or “is not” when comparing with None.

In the example below, we want to test

if True == Trueif the test returns

True, then- print “

Condition is True”

- print “

if the test returns

False, then- print “

Condition is False”

- print “

condition = True

if condition: # <==> if condition == True:

print('Condition is True')

else:

print('Condition is False')

Try changing the value of

conditiontoFalsein the example above

Here is another example.

dividend = 56

divisor = 12

if divisor != 0:

print(dividend, '/', divisor, "=", dividend/divisor)

else:

print("Sorry, can not be divided by 0")

Comparison Operators#

We used the equality == operator above to check if a condition was equal == to True.

Notice the equality is indicated by double equal signs

==.

A variable assignment is indicated by a single equal sign =.

| Name | symbol |

|---|---|

| equality | == |

| inequality | != |

| less than | < |

| less than or equal | <= |

| greater than | > |

| greater than or equal | >= |

| membership | in |

Let’s look at some examples of other comparison operators.

- Inequality

!=

>>> 5 != 5

False

- Less than

<

>>> 5 < 8

True

- Membership

in

>>> 5 in (2, 4, 5)

True

Multiway Branching#

Multiway Branching allows testing of multiple conditions in a sequence by the statement elif.

elif goes between the if and the else statements.

elifstands for if else.elifis used to tie multipleifstatements together.We can have any number of

elifstatements as we like.It will execute the first test it passes, in the case

True.- Below, no conditions are met until it reaches

color == "yellow".

- Below, no conditions are met until it reaches

Notice how we are using the f-string format to pass the

{color}variable.

color = "yellow"

if color == "red":

print(f"Apples are {color}")

elif color == "green":

print(f"Lemons are {color}")

elif color == "yellow":

print(f"Bananas are {color}")

else:

print(f"I can not match the color {color}")

While and for loops#

Loops are expressions allowing us to repeat other commands rapidly.

Python has two main types of loops, while and for loops.

while loops are for general purpose, and for loops are mainly used to execute blocks of code on iterable items like lists, Tuples, dictionaries, etc.

while loops#

As the most general of the iterating tools, with a test statement at the top.

The while loop will continue to execute the code block beneath it until the test at the top of the while loop condition changes.

Note: To execute a loop in a Python Interactive Session, we need to add four spaces for indentation below the header and press the

Enterkey twice after the last line of the loop.

In the example below, the loop starts with:

while.And the test is:

counter <= 10.

And the colon signifies end test statement:

:

Any indented code below this line is part of the loop.

The

print()function will print an asterisk,*, will be multiplied by the value ofcounter:print('*' * counter).

Then, the value of

counterwill be updated by a count of 1.counter += 1.

It will continue to execute updating

counteruntil the counter value is less than or equal to 10.

>>> counter = 1

>>> while counter <= 10:

... print('*' * counter)

... counter += 1

*

**

***

****

*****

******

*******

********

*********

**********

>>>

while infinite loop#

There are times when we could write an infinite loop without any methods to stop the loop.

The loop will continue to run forever. We would not want this unless we use other loop statements to stop the loop as the brake statement.

To stop an infinite loop, press the

Ctrl-Ckeys

>>> while True:

... print('I am an infinite loop')

I am an infinite loop

I am an infinite loop

I am an infinite loop

# ... and so on

The for loop#

For loops, are iterators used to go through items in any sequence they work with Tuples, Lists, Dictionaries, Strings, Files, and other iterables.

The for line is the header of the loop; this is where we create variables to hold items from the iterable.

The example below uses the variable fruit to temporarily hold each item as the loop goes through each item in the list.

Then the fruit variable is tested against the conditional statement.

all_fruits = ('Bananas', 'Apples', 'Lemons', 'Grapes', 'Nectarines', 'Oranges')

for fruit in all_fruits:

if fruit == 'Grapes':

print(f'* {fruit} Out of stock!')

else:

print(f'{fruit}')

'''

Bananas

Apples

Lemons

* Grapes Out of Stock!

Nectarines

Oranges

'''

The range() function creates an iterable, not a list.

r = range(0, 5)

print(r)

print(list(r))

range() generates values on demand and does not store them in memory.

forloops can also use loop statements, explained below.

enumerate() returns both the index and the value of an iterable.

colors = ["red", "blue", "green"]

for index, color in enumerate(colors):

print(index, color)

enumerate() is preferred over manually counting with a variable.

Loop statements#

break, continue, and the Loop else statements specific to loops in Python.

| Statement | Description |

|---|---|

break | Jumps out of the loop ~ “quits” the loop statement |

continue | Jumps to the top of the loop ~ to the loop’s header line |

else: | Only if the loop is exited normally ~ i.e., without using break |

continue#

We may write a loop that counts to ten, but we only want it to print the even numbers.

Look at the comments in the code below, prefixed by #, for a line-by-line explanation.

n = 0

while n <= 10: # test for n

n += 1 # adds 1 to n and reassigns

if n % 2 != 0: # if n is not even

continue # go to the top

print(f'{n}', end = ' ') # else print even number

# end=' ' prints n horizontally

# 2 4 6 8 10

break and else#

We may want a loop that tests n to be less than or equal to 20, if n is an even number and greater than 17, then print something and break. If the condition is not met, that is, unable to find/reach an even number greater than 17, then else statement will be printed.

n = 0

while n <= 20:

n += 1

if n % 2 == 0 and n > 17: # the first n divisible by 2 greater than 17

print(f'{n} is 18!') # will print

break # and break (not execute else)

else: # If the test in while were less than 18

print(f'{n} is not 17') # then this would print

# 18 is 18!

Loops, non-primitives, and conditional statements are powerful tools.

Introduction to Python Functions#

Functions are a way to organize code into reusable blocks of code. They are easy to implement yet flexible and powerful.

We already have used some of Python’s built-in functions, such as:

print()At its most basic level allows us to print to screen.str()Allows to set the Type of an object to a string.

We know if we “call” the print function and “pass” a string, “Hello world” as an “argument”, the program will print the string to the screen.

>>> print('Hello world')

Hello world

For example we can change the type of an integer with the built in function str() function.

>>> str(1)

'1'

>>>

we can combine functions to make them more powerful

>>> print(type(1))

<class 'int'>

>>> print(type(str(1)))

<class 'str'>

>>>

Using built-in functions has been like magic. We pass some arguments and it returns the results.

The Python core development team wrote all the built-in functions; we can get a list of all the built-in functions from the Python documentation .

We can also write custom function, making python even more flexible and powerful.

All scripts in Python are considered ‘modules’, it allows programmers to write small pieces of code and call them from other scripts.

Anatomy of a function#

We understand the idea of using the built-in functions; they are repetitive tasks we would like to call and reuse without copying and pasting all over our scripts.

For example, we may have a block of sequential code that we would like to reuse and call it when we need it.

We may want to print to screen a string with a line above and below to bring attention to it.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Welcome to my house, take your shoes off

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Sequentially we might do something like this, but every time we want to use this block of code, we have to copy it and past it where we want to use it.

my_string = 'welcome to my house, take your shoes off'

print('~' * len(my_string))

print(my_string)

print('~' * len(my_string))

If we use the code above in different parts of our script, it becomes difficult to maintain, as we have to update all the instances of our code block.

By turning our code block into a function, we can add flexibility to our code.

Function structure#

Let’s break down the structure of a function and learn how to write one.

Defining our function#

We first have to define a function with a keyword and name.

def function_name():

First, we need to define a function by using the keyword

def

Add space and enter a function name

def function_name

We need to follow the function name with parenthesis

def function_name()

We must end the definition line with colon

def function_name():

Function indentation formatting#

We let Python know which code belongs to a particular function by indenting it below the function definition.

In Python, the standard indentation is four spaces.

# code does not belong to the function

def function_name([argument], [argument]):

statements

statements

[return result]

# code does not belong to the function above

Now, we know the proper function indentation format, let’s continue with our function.

Function docstring#

Right below the function definition we place our docstring.

A docstring is a string literal that occurs as the first statement in a module, function, class, or method definition.

- It is intended as formatted documentation for that module, function, class, or method.

- Useful as we read a program and try to understand it or remember what we wrote.

- Useful if we import a module into a script. Code editors can display the docstring of a function.

def function_name():

""" DocString, write a brief description of the function"""

- Right below the definition, indent our code.

- Enter the docstring with-in triple quotes.

“A universal convention supplies all of maintainability, clarity, consistency, and a foundation for good programming habits too. What it doesn’t do is insist that you follow it against your will. That’s Python!” ~ Tim Peters on comp.lang.python, 2001-06-16

Function code block#

Write each line of our function code, starting with indentation.

def function_name():

""" DocString, write a brief description of the function"""

a = n1

b = n2

c = a + b

If a function does not explicitly return a value, it returns None.

Return the function value/s#

To get the result from our function, we must tell the function to return it; by using the keyword return followed by the result.

def function_name():

""" DocString, write a brief description of the function"""

a = n1

b = n2

c = a + b

return c

In the last line of our function, type the keyword return followed by the value to return. It will return a value that can be used for other operations, like print to screen.

Note, a function can execute other functions. We will see an example below.

Our first basic function#

If we turn our sequential code into a function, we can call it from anywhere in our script.

There are some simple steps we have to take to turn our block of code into a function.

my_string = 'Help me write a function.'

def header():

""" DocString: write a brief description """

print('~' * len(my_string))

print(my_string)

print('~' * len(my_string))

Our header() function can be called from any place in the script, even from other scripts, and it will execute the indented code block.

We call our function like any other function. In this particular case, the print statements are within the function. All we have to do is call it, and it will print to the screen automatically.

>>> header()

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Help me write a function.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The function formats and prints the string passed as an argument.

Arguments in functions#

We can make our function more flexible if we could use it like the print() function, where we pass the message, and it does the rest.

In python, we can pass arguments to a function.

We can also pass three types of arguments, the positional argument, key argument, and arbitrary argument.

In this lesson, we will introduce the positional argument

Positional function argument#

Positional arguments are the most common in functions.

In later lessons, we will cover the other types of arguments.

A function can take any number of positional arguments they have to separate them by commas. def function(argument1, argument2):

We must pass the values of the argument in the correct order, hence the name positional. We can even pass other functions as an argument.

But let’s start by passing a single positional argument.

- Add the argument name

message; inside the parenthesis of our function definition. - Assign that argument name to all the operations that need to make use of it.

def header(message):

print('~' * len(message))

print(message)

print('~' * len(message))

We name the argument ‘message’; whatever object we pass as an argument will be formatted.

- Let’s call our function with the positional argument in it.

- Note, we could assign the string to a variable and pass that variable as the argument.

>>> header('Welcome to my card game')

Now the header() function will return the following:

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Welcome to my card game

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Python passes references to objects into functions.

def add_item(lst):

lst.append(4)

items = [1, 2, 3]

add_item(items)

print(items)

Mutable objects can be modified inside a function. Immutable objects cannot be changed in place.

Having turned our code block into a function gives us a few advantages.

- Centralized code

- Modify once, easy to maintain

- Call it from anywhere, even from other scripts

Functions are powerful programming tools and offer enormous flexibility.

Exercises#

Write a function to do the following. We may want to write the sequential code then we can turn our code block into a function.

- Find the Max of three numbers.

- Sum all the numbers in a list.

- Multiply all the numbers in a list.

- Reverse a string.

- Accepts a string and calculates the number of upper case letters and lower case letters.

Exception Handling#

During program execution, runtime errors can occur.

Exceptions allow a program to handle these errors without crashing.

try / except#

The try block contains code that may raise an exception.

The except block handles the error if it occurs.

try:

number = int("abc")

except ValueError:

print("Conversion failed")

If an exception occurs inside the try block, the corresponding except

block is executed.

except with error object#

The exception object can be accessed using as:

try:

number = int("abc")

except ValueError as e:

print(e)

finally#

The finally block is always executed, whether an exception occurs or not.

try:

number = int("10")

except ValueError:

print("Conversion failed")

finally:

print("Execution finished")

Variable Scope in Python#

In Python, the scope of a variable defines where the variable is visible and where it can be accessed or modified in a program.

Python uses a lexical (static) scoping model. This means that the scope of a variable is determined by the location where it is defined in the source code, not by where a function is called.

Python follows a simple and predictable scope lookup order:

• Local scope: variables defined inside a function • Enclosing scope: variables defined in an outer (enclosing) function • Global scope: variables defined at the top level of a module • Built-in scope: names provided by Python itself (e.g. len, int, print)

This model is commonly referred to as the LEGB rule.

Built-in names are resolved last in the scope lookup order.

def test():

print(len("hello")) # len comes from the built-in scope

test()

⚠️ Avoid overwriting built-in names, as this can break scope resolution.

Understanding scope is essential to avoid unexpected behavior, especially in larger programs, data pipelines, and AI training code.

Incorrect scope usage can lead to: • hidden bugs • unintended global state • hard-to-debug side effects

Let’s look at how scope affects variable visibility in practice.

x = 10

def test():

x = 5

print(x)

test()

print(x)

x = 10

def change():

global x

x = 20

def outer():

y = 5

def inner():

nonlocal y

y = 10

inner()

print(y)

outer()

⚠️ Global variables should be avoided in AI training loops and data pipelines, as they can introduce hidden state and hard-to-track bugs.

Lists, Tuples, and Dictionaries#

So far, we have been storing a single value per variable. What if we need to store multiple values and assign them to a variable.

Python offers a series of non-primitive containers for storing multiple values into different containers.

We are going to cover Lists, Tuples Dictionaries. They are non-primitive mutable types, except for Tuples which are immutable in the same way strings are immutable.

- Non-primitive types are containers or “lists” for multiple objects.

- All except Tuples are mutable, meaning they can be updated.

- Any non-primitive can have multiple types in it int, str, float, and so on.

Tuples#

A tuple is an immutable list of objects placed within the parenthesis.

Below would be an empty tuple.

tup_1 = ()

A tuple containing one item; must be followed by a comma. This tells python the single object in parenthesis is a tuple.

tup_2 = (1,)

A tuple can have any type of Python object.

tup_2 = (1, "house", 4.5, True)

Accessing items in a tuple is easy by slicing the tuple.

Here we are calling the third item in the tuple by using index number 2.

>>> tup_2[2]

4.5

>>>

Much like slicing a string, we can call a range by specifying a start and end.

>>> tup_2[1:3]

('house', 4.5)

>>>

We can also iterate through a tuple with a for loop.

>>> for i in tup_2:

... print(i)

1

house

4.5

True

Lists#

Lists are very similar to tuples, except lists are mutable or editable. Lists, in theory, are slower than tuples.

Lists work well with appending and deletions; or information that changes. Lists do use up more memory.

Lists are inside brackets. A list with a single item does not need a comma at the end as a tuple does.

lst1 = [1]

A list like other non-primitive objects in Python can contain different type objects.

A list can have other non-primitive objects, such as lists and tuples.

lst2 = [1, "4", True, 3.4, [1, 2, 3, 4]]

Lists can be edited; by using many built-in list methods.

Here are some of the more popular ones. Other built-in functions can be used with a list not cover here.

append#

The .append() method adds an object to the end of a list.

>>> lst1.append('second')

>>> lst1

[1, 'second']

>>>

insert#

With the .insert(p, o) method, we can add an object and the position by first adding the index position followed by the object to insert.

>>> lst2.insert(3, "new")

>>> lst2

[1, '4', True, 'new', 3.4, [1, 2, 3, 4]]

>>>

extend#

This method allows us to join two lists together.

>>> lst3 = ["old", '6', 7]

>>> lst2.extend(lst3)

>>> lst2

[1, '4', True, 'new', 3.4, [1, 2, 3, 4], 'old', '6', 7]

>>>

remove#

Removes an object from a list with an x value; if not found, Python will cast an error.

>>> lst2.remove('old')

>>> lst2

[1, '4', True, 'new', 3.4, [1, 2, 3, 4], '6', 7]

>>>

pop#

.pop() will remove the last item of a list and return it.

>>> lst2.pop()

7

>>> lst2

[1, '4', True, 'new', 3.4, [1, 2, 3, 4], '6']

>>>

We can give the index position of an item, and the pop method will remove it.

>>> lst2.pop(3)

'new'

>>> lst2

[1, '4', True, 3.4, [1, 2, 3, 4], '6', 7]

>>>

clear#

The clear method will remove all items from a list.

>>> lst4 = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

>>> lst4.clear()

[]

>>>

count#

The count method will return the number of times a particular item is on the list.

>>> lst_c = [5, 6, 5, 8, 8, 5, 7, 2, 5]

>>> lst_c.count(5)

4

>>>

Dictionaries#

Dictionaries are mutable non-primitive containers, much like a list.

They consist of key: value pairs. The key must be unique, where the value can be anything. Dictionaries use curly brackets.

dct = { "key": "value" }

A reservation application could use a dictionary to manage structured data.

>>> dct1 = {'reservation': 545527,

'table': 22,

'party': 5,

'date': "4/12/2022"

}

We access dictionaries by using keys; we do not use an index like in a string.

>>> dct1['reservation']

545527

>>>

For instance, if we need to update the number of people in the reservation, we would assign a new value to the ‘party’ key.

>>> dct1['party'] = 4

>>> dct1['party']

4

If we needed to add special accommodations to our reservation, we could add them to the dictionary.

>>> dct1['spl_acc'] = "One party with a peanut allergy"

>>> dct1

{'reservation': 545527, 'table': 22, 'party': 4, 'date': '4/12/2022', 'spl_acc': 'One party with a peanut allergy'}

Inversely we could remove an item by using the del statement.

>>> del dct1['spl_acc']

>>> dct1

{'reservation': 545527, 'table': 22, 'party': 4, 'date': '4/12/2022'}

Dictionary built-in methods#

Much the same way strings and lists have methods; dictionaries also have their own methods.

Some dictionary methods are very similar to string methods. Lists, for instance, the .clear() list method works the same way in dictionaries.

get#

We use the .get() method to get the value of a particular key.

>>> dct1.get('party')

4

>>>

items#

I will return a list of `key: value pairs from a dictionary.

>>> dct1.items()

dict_items([('reservation', 545527), ('table', 22), ('party', 4), ('date', '4/12/2022'), ('spl_acc', 'One party with a peanut allergy')])

>>>

keys#

We can get a list of all the keys from a dictionary by using the .keys() method.

>>> dct1.keys()

dict_keys(['reservation', 'table', 'party', 'date', 'spl_acc'])

>>>

values#

Equally, we can get all the values from a dictionary by using the .values() method.

>>> dct1.values()

dict_values([545527, 22, 4, '4/12/2022', 'One party with a peanut allergy'])

>>>

update#

To update or merge dictionaries we could use the .update() method.

>>> dct1.update(table=25, date='5/12/2022')

>>> dct1

{'reservation': 545527, 'table': 25, 'party': 4, 'date': '5/12/2022', 'spl_acc': 'One party with a peanut allergy'}

Python offers many options to manage data. The challenge for a starting developer can be remembering all the methods available.

Introduction to Object Oriented Programming#

As a multiparadigm language Python offers Object Oriented Programming (OOP) and procedural programming. As Python programmers, we use Objects all the time. Everything in Python is an Object from primitives to non-primitive. Objects are categorized under different classes. A Python class is part of Object Oriented Programming.

OOP is used by developers who have a solid idea of what they want to deliver, usually for writing large applications providing a OO architecture for others to use and inherit from.

This is an introductory course into Object Oriented Programming classes; this course will let us see how Python uses Object Oriented Programming. We will have a chance to write our custom classes, serving as a good entry point into the large subject of OOP.

Built-in methods#

Python offers extra functionality such as methods accomplished by assigning each entity attribute through type classification. All possible by using Object Oriented Programming.

For example, the number 1 is an object belonging to the int (or integer) class.

>>> type(1)

<class 'int'>

>>>

Python classifies a list as part of the list class, which offers methods capable of modifying a list.

>>> type([1, 'tea', 3.5])

<class 'list'>

>>>

We often use methods in the programs we write, such as list and string methods; these methods are available to the class objects.

For example, we can make a string all upper-case, by using the string .upper() method. The str class returns an all-upper-case string when this method is applied.

>>> "Hello world".upper()

'HELLO WORLD'

>>>

For instance, if we try to use a string method to modify a list, we get an error saying a list object doesn’t have any 'upper' attributes.

>>> [1, 'tea', 3.5].upper()

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

AttributeError: 'list' object has no attribute 'upper'

>>>

We can write our own classes also including custom attributes and methods, by using Object Oriented Programming.

Creating custom classes#

Programs are designed to manipulate data in a meaningful way. For large or more modular computer applications, we can use Object Oriented Programming, helping manage the applications we write. With OOP we can also write reusable structured code.

This modularity gives us the ability to keep our code organized, easy to read and access, but it requires some planning.

Class#

Classes are blueprints to built data and functionality in a single container. A class has several members, including a constructor, instance attributes, class attributes, and methods.

Let’s begin by defining our first class, an empty class, as it doesn’t do anything. Class naming has its convention, normally capitalizing the first letter of the class name. If we use more than one word, we capitalize the first letter of each word. This naming convention is called “PascalCase”.

>>> class CrazyString:

... pass

...

>>>

Once we create a new class, we can make new objects or instances based on that class. The new object will inherit any attributes, variables, or methods found in the class. We can create any number of objects from a class.

Let’s make a new object using the CrazyString class. First, write the name of the class followed by a parenthesis and assign it to a variable.

>>> cs1 = CrazyString()

>>>

We can attach data to the newly created object by calling the object; a dot followed by the variable name and assigning a value to it. The class we created will do work on strings, so we pass a string as a value.

>>> cs1.string = "Hello World"

>>>

The value “Hello World” was assigned to the cs1.string object.

We can check its existence by calling the object. We should get the value we assigned to it in return.

>>> cs1.string

'Hello World'

>>>

We could create a separate variable, name string, attach a value to it, and it will be kept separate from the cs1.string variable.

>>> string = "I stand alone"

>>> cs1.string

'Hello World'

>>> string

'I stand alone'

>>>

We could create a new CrazyString object and add the same variable name. All three string variables would be kept in separate memory spaces.

- cs1.string

- cs2.string

- string

>>> cs2 = CrazyString()

>>> cs2.string = "I am cs2"

>>> cs2.string

'I am cs2'

>>> cs1.string

'Hello World'

>>> string

'I stand alone'

>>>

We can use classes to create multiple objects; each object can have different values. To make full use of a class we give it the ability to initialize, hold methods, attributes and documentation.

Class initialization#

We can initialize a class with the init method. Every time a new instance of a class is created the init method executes.

The process is also called a constructor in Object Oriented Programming, allowing the class to initialize its attributes.

Methods are functions inside a class created very similarly to regular built-in functions.

Let’s write the init method inside our CrazyString class.

We define a method the same way as a function by using the keyword def. We add __init__() constructor, with double underscores, to initialize our objects. The first parameter has to be self, referring to the initialized object.

After self we can add the string parameter to hold the string argument.

We then store the values to fields in the object by typing self, dot, the field name, and then assign it a value, self.string = string.

class CrazyString:

def __init__(self, string):

self.string = string

We can test our class by creating an object and assigning an argument to it in the form of a string.

crazy_str = CrazyString("Hello world")

print(crazy_str.string)

# Hello world

Programming a class method#

Now let’s add a method to our CrazyString, it will allow us to capitalize every vowel in our string.

Start by defining our method the same way we define a function.

- We can call the method

hump_bump(): - Only going to pass

selfas an argument, referring to any object created with this class. - Add a short Docstring.

- Assign the

self.stringobject to a variable, call itstr_holder. This variable holds any string object we pass to thehump_bumpmethod. - Create a tuple with all the vowels and assign it to a variable, creatively called

vowels. - Finally, we return the new string with all vowels in upper-case, as in the list comprehension executing our expression.

class CrazyString:

def __init__(self, string):

self.string = string

def hump_bump(self):

"""Converts vowels to upper case in a string"""

str_holder = self.string

vowel = ('a', 'e', 'i', 'o', 'u')

return "".join([i if i not in vowel else i.upper() for i in str_holder])

Using the new class method#

We can now use the CrazyString hump_bump method. We first need to create an instance of the CrazyString class.

- Start by creating a string and assigning it to the

the_strvariable. - Create an instance of the

CrazyStringclass and pass the string as an argument. Assign the expression to thecrazy_strvariable. - We can now use any method in the CrazyString class in the object created, as long as it is a string.

- Add the dot method to our

crazy_strobject and print it.

the_str = "Three Greek trees grew from seeds. Freewheeling, the feet of a giant green toad landed on the trees."

crazy_str = CrazyString(the_str)

print(crazy_str.hump_bump())

# ThrEE GrEEk trEEs grEw frOm sEEds. FrEEwhEElIng, thE fEEt Of A gIAnt grEEn tOAd lAndEd On thE trEEs.

Under the CrazyString class, we can have many related methods, all related to strings, as the idea is to keep related logic together.

If we create an instance of the CrazyString class with a list of integers and we try to use the hump_bump method, we would get a type error as it would expect a string, not integers.

Class attribute#

Class attributes are for storing variables and constants shared by a particular class. Let’s use our CrazyString class to illustrate.

We want to create a new method, one that counts all the vowels in a string. We have a problem since the vowel tuple is under the hump_dump method and not available to others.

We can solve this by creating another copy of the vowel tuple under the new method, not an ideal solution. We want to minimize having multiple instances of the same data.

We make the vowel tuple available to the entire class by making it a class attribute. By placing the vowel tuple right under the class name, we make it available to the CrazyString class.

class CrazyString:

vowel = ('a', 'e', 'i', 'o', 'u')

We also have to modify the hump_dump method to avoid any errors. We reference the vowel tuple in the list comprehension, add the self. in front of the vowel attribute.

"".join([i if i not in self.vowel else i.upper() for i in str_holder])

Let’s create a new method to count the number of vowels in a string in our CrazyString object.

- Underneath our

hump_dumpmethod, define a new method by calling itvowel_counter. - Create the variable

str_holderto hold the string. - Create a list with only the vowels in the string, then use the

len()function to return the number of vowels found.

class CrazyString:

vowel = ('a', 'e', 'i', 'o', 'u')

def __init__(self, string):

self.string = string

def hump_bump(self):

"""Converts vowels to upper case in a string"""

str_holder = self.string

vowel = ('a', 'e', 'i', 'o', 'u')

return "".join([i if i not in self.vowel else i.upper() for i in str_holder])

def vowel_counter(self):

"""counts number of vowels in a string"""

str_holder = self.string

return len([i for i in str_holder if i in self.vowel])

Let’s call both methods, one to upper case all the vowels and the other to return the number of vowels in a string. Both class methods will use the vowel class attribute.

the_str = "How many vowels in this string"

crazy_str = CrazyString(the_str)

print(crazy_str.hump_bump())

print(crazy_str.vowel_counter())

The .hump_bump() and .vowel_counter() methods will print the following.

HOw mAny vOwEls In thIs strIng

7

The destructor method#

Unlike the __init__ method, used to construct an object, we can also use the __del__ method to destroy an object.

In Python is recommended only to use the destructor on special occasions and allow the “garbage collector” to take care of discarded objects.

To illustrate the destructor, we can add it right under the __init__ method.

class CrazyString:

vowel = ('a', 'e', 'i', 'o', 'u')

def __init__(self, string):

self.string = string

def __del__(self):

print("Object destroyed")

def hump_bump(self):

"""Converts vowels to upper case in a string"""

str_holder = self.string

vowel = ('a', 'e', 'i', 'o', 'u')

return "".join([i if i not in self.vowel else i.upper() for i in str_holder])

def vowel_counter(self):

"""counts the number of vowels in a string"""

str_holder = self.string

return len([i for i in str_holder if i in self.vowel])

If we reassign a new value to the same variable holding our object, it would automatically call the destructor. In our case, after removing the object, the method will print “Object destroyed”.

the_str = "How many vowels in this string"

crazy_str = CrazyString(the_str)

crazy_str = 'value reassignment'

# Object destroyed

Class inheritance#

Thus far, we have worked with a single class, but we can create a new class borrowing from a parent class. It enables us not to have to rewrite a class with all the same components. We can expand on it by creating a child class and inheriting it from a parent class.

Let’s write a new class including a method to modifies vowels in a string. We already have the CrazyString or parent class available. All we do is write a child class that inherits from the parent class, CrazyString.

Child and parent classes#

To illustrate parent child classes, we create a new class adding parenthesis at the end.

In the parenthesis, we pass the class name we want to inherit from or the parent class name.

class CsReplace(CrazyString):

pass

Now, the child class can execute the methods from the parent class. The child class inherited the properties from the parent class.

This is powerful, as it allows us to write less code and create continuity in our code.

Let’s create an instance of the new class and call one of the methods from the parent class .hump_bump().

class CsReplace(CrazyString):

pass

cr = CsReplace("Child string")

print(cr.hump_bump())

# ChIld strIng

To illustrate the inheritance of a child class from a parent class. Let’s create a method in the CsReplace class. The new class method will replace all the vowels with @ symbol. We will make a call to the CrazyString attribute vowel.

Let’s start by naming the new method switch, assigning the self variable as an only parameter, and finally returning the new string with all the vowels replaced with the @ symbol.

class CsReplace(CrazyString):

def switch(self):

return "".join([i if i not in self.vowel else "@" for i in self.string])

We can now call the .switch() method and any other methods from the CrazyString class by creating a CsReplace object.

cr = CsReplace("Let's call the inherited methods")

print(cr.hump_bump())

print(cr.switch())

print(cr.vowel_counter())

# LEt's cAll thE InhErItEd mEthOds

# L@t's c@ll th@ @nh@r@t@d m@th@ds

# 9

Conclusion#

Now we should understand how methods work with classes and on objects, how they work with-in python. We also learn how to create custom Python classes with attributes and methods. We also covered what parent and child objects are and how inheritance works.

Object Oriented Programming is a large subject matter, with many details and years to master, but this class serves as an entry point to Object Oriented Programming. From this point, we can branch out and start studying other related subjects.

© 2025 Oskar Kohler. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.Hinweis: Der Text wurde manuell vom Autor verfasst. Stilistische Optimierungen, Übersetzungen sowie einzelne Tabellen, Diagramme und Abbildungen wurden mit Unterstützung von KI-Tools vorgenommen.